"Sincerely, your beloved son...."

One of Chuck Berry's greatest car songs took the form of a letter to Dad

Chuck Berry released "Dear Dad" on March 15, 1965, his 38th single for Chess. It cracked the Top 100, idling at the 95 spot for a month. It's always been one of my favorite Berry tunes, a post-peak gem that tells a witty story with a great punch line while rocking slyly. Berry recorded the tune on December 16, 1964 at the Ter-Mar Recording Studio at 2120 South Michigan Avenue, in Chicago, with a band led by the guitarist Jules Blattner, who Berry knew from seeing him play in the St. Louis area. With Blattner, bassist William L. Bixler, and drummer Howard Jones backing Berry, the performance motorvates along nicely, Jones's chugging backbeat especially propulsive as Berry plays a groovy and grooving syncopated car-horn riff in the verses (there is no chorus); somehow the thing both rocks and teeters. (I recently scored a copy of the 45, posted below, and the mono mix puts the anemic stereo mix to shame. Berry and the band also cut the loose-limbed "I Want To Be Your Driver" at these sessions, both tunes appearing on Chuck Berry in London in 1965.)

In the tradition of the epistolary, Berry writes from the perspective of Henry Ford's son, who's desperate for a new car but who's afraid to ask for one, Berry merging the idiosyncratic with the universal, his super power. (He also knew that the family dynamic is one of the great issues in American art, the rock and roll 45 no less.) The premise alone—that even Ford's son is relegated to driving a piece of shit like every other teenager in America who can't afford a better car—is hilarious and fresh. Junior knows that if he's going to approach the old man, then his argument better be tight. He respectfully placates Dad at first ("don't be mad") and then in a long anxious breath lays out the dire mechanical issues, with one hilarious image-phrase after another: I might as well be walking; if I ain't going downhill I'm out of luck; if I push to 50 this here Ford will nosedive; cars whizzing past me look like I'm backing up. Fantastic. The whole argument's over in under two minutes. We never get Pop's return letter.

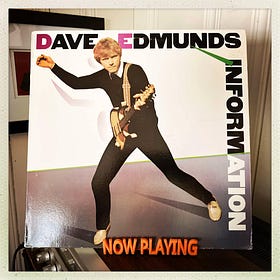

Berry was infamous taskmaster to his pickup bands, who were often treated churlishly, yet it's virtually impossible to hear this and not imagine grins on all of the musicians' faces as they rev tup. It's an essentially perfectly written rock and roll song; though the band sounds a tad underrehearsed, and the sloppy-even-for-1960s-Berry guitar solos feel a bit tossed off, to my ears the off-the-cuff performance conjures the car itself coming apart at the seams. (Like many rock and roll fans of my generation, I was introduced to the song via Dave Edmunds, who released a version on D.E 7th in 1982. His take is respectful, yet just as wittily rocking: he adds some period reverb and tidies up Berry's solos, offering one of them to pianist Geraint Watkins, whose winking glissando in the third verse mimics the Ford's "nose dive.")

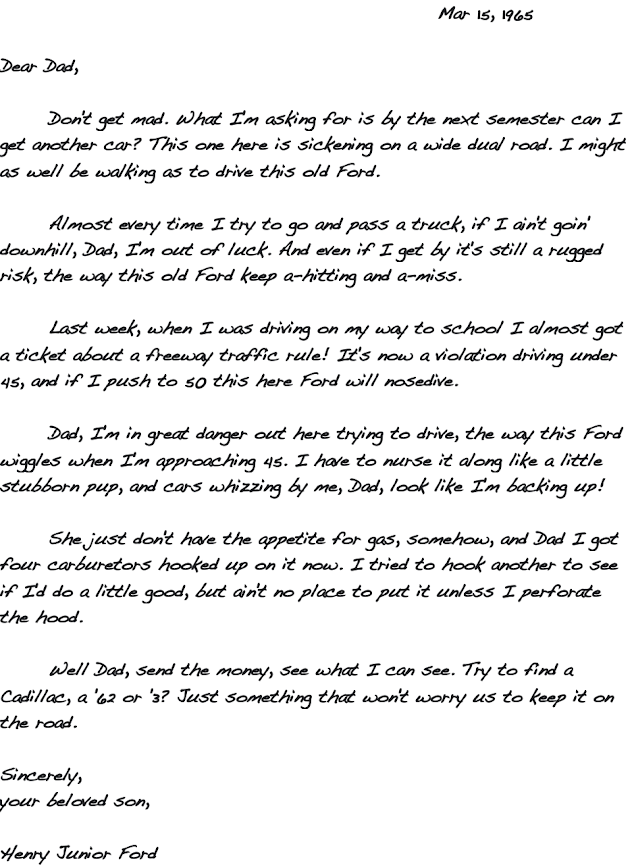

Casting around for some diversions as I recover from Covid, I got the idea of transposing the song's lyrics as a hand-written letter. Unsurprisingly, the translation from lyrics sheet to scrawled note was effortless, Berry's vernacular perfectly capturing that cracking voice of an average teenager sweating out a letter to a parent asking for something they know they probably won't get. Read it aloud without the song—it works and sounds like a letter, too, so tuned was Berry's ear to the music in everyday speech. Berry's genius was so distinctive and dimensional as to seem epic, larger-than-life, when really what he did—superbly, poignantly, hilariously, and seemingly casually—was to capture that male adolescent perennially poised between stuck-at-home and bound-for-the-road, as American, as universal, really, as anything there is. As Berry himself once said, "Everything I wrote about wasn't about me, but about the people listening."

See also:

The promised land callin'

"But finally, I suppose, the most difficult (and most rewarding) thing in my life has been the fact that I was born a Negro and was forced, therefore, to effect some kind of truce with this reality."

Chuck Berry in the dark

Sometime in the 1990s I was listening to a bootleg CD of the Beatles’ late-1966 recording sessions for “Strawberry Fields Forever.” Buried deep near the end of one take, I heard what sounded like a random Chuck Berry lick played by George Harrison, a lone formalist stay against the chaos that John Lennon was brewing in his deeply inward, trippy evocatio…

Slipping away

Weather ignores borders—rain in northern Illinois is likely falling in southern Wisconsin, too—just as popular music leaks through the boundaries that separate decades. An arbitrary gathering of years, a decade implies that a Zeitgeist emerges with calendar regularity, when most of what we associate with a given ten-year span occurs at a later perspecti…

It’s a gem. I first heard it when the boxed set came out. Named my dog after one of his songs.