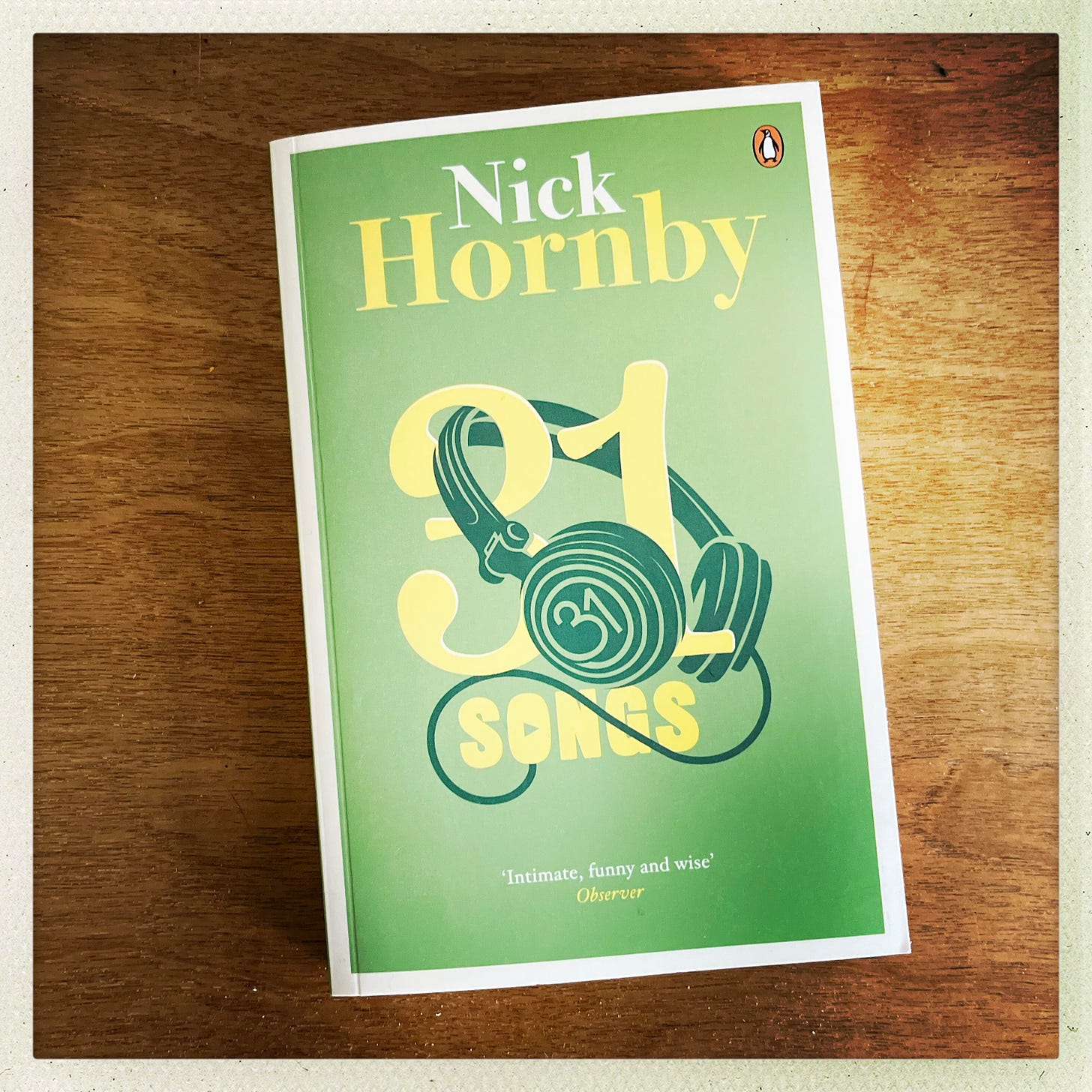

In the introduction to 31 Songs, a gathering of essays about songs he loves, Nick Hornby writes about the nature of music writing. In 2001, Hornby staged a benefit show at the Hammersmith Palais in London; among the bands performing was Teenage Fanclub, who as it happened were rehearsing their tune “Your Love Is The Place Where I Come From” at the precise moment Hornby arrived at the venue. At the time, Hornby felt, quite naturally, that whenever he’d hear that song in the future he’d remember that moment and that place. How could it be otherwise, he wonders.

A strange thing occurred when Hornby sat down to write 31 Songs. “Initially, when I decided that I wanted to write a little book of essays about songs I loved (and that in itself was a tough discipline, because one has so many more opinions about what has gone wrong than about what is perfect), I presumed that the essays might be full of straightforward time-and-place connections like this,” he writes, adding, “but they're not, not really.”

In fact, “Your Love Is The Place Where I Come From” is just about the only one. And when I thought about why this should be so, why so few of the songs that are important to me come burdened with associative feelings or sensations, it occurred to me that the answer was obvious: if you love a song, love it enough for it to accompany you throughout the different stages of your life, then any specific memory is rubbed away by use.

Hornby goes on to imagine hearing Bruce Springsteen’s “Thunder Road” the year it was released “in some girl’s bedroom.” If she and the song vanished from his life after that day, hearing it again years later would bring back for him only stray details (“the smell of her underarm deodorant”) embedded in a foggy memory. “But that isn’t what happened; what happened was that I heard ‘Thunder Road’ and loved it, and I’ve listened to it at (alarmingly) frequent intervals ever since. ‘Thunder Road’ really only reminds me of itself, and, I suppose, of my life since I was eighteen—that is to say, of nothing much and too much.” He adds a bit later: “I wanted mostly to write about what it was in these songs that me love them, not what I brought to the songs.”

This struck a chord with me (pun intended). Of course, songs are time machines. Listening to a tune—deliberately, or unbidden, in a store, a bar—can bring us back to a time and place in alarming fashion. The effects can be blissful, or traumatic, depending. Yet I’m intrigued by Hornby’s argument: what accounts for a song that transcends that time and place, that renews itself with each listen, shedding that stubborn time-and-date stamp, and comes to matter, again, wherever—and whoever—we are? Sometimes a song we carry around can fall out of fashion, like the clothes we wore or our hairstyle; others we carry are timeless.

“Songwriting is a burst of inspiration and then a long bit of work and a tremendous bit of desperation.”

That’s the great Donovan in his memoir Autobiography of Donovan: The Hurdy Gurdy Man. It’s one of my favorite observations about songwriting, a process that I admire and am enthralled with for its mystery. A revelation followed by a spell of hard work feels right, ordinary, even—that’s any reputable contractor’s afternoon when faced with a mysterious water leak. It’s that “desperation” that interests and eludes me. What does Leitch mean? The agony of Does this song work? The anxiety of Will anyone like it? Or is he alluding to desolation after failing, again, to accurately translate sense and feeling into words and music? Someone said that the longest journey is from the brain to the page; I forget who but it doesn’t really matter, because the epiphany’s struck every writer at least once.

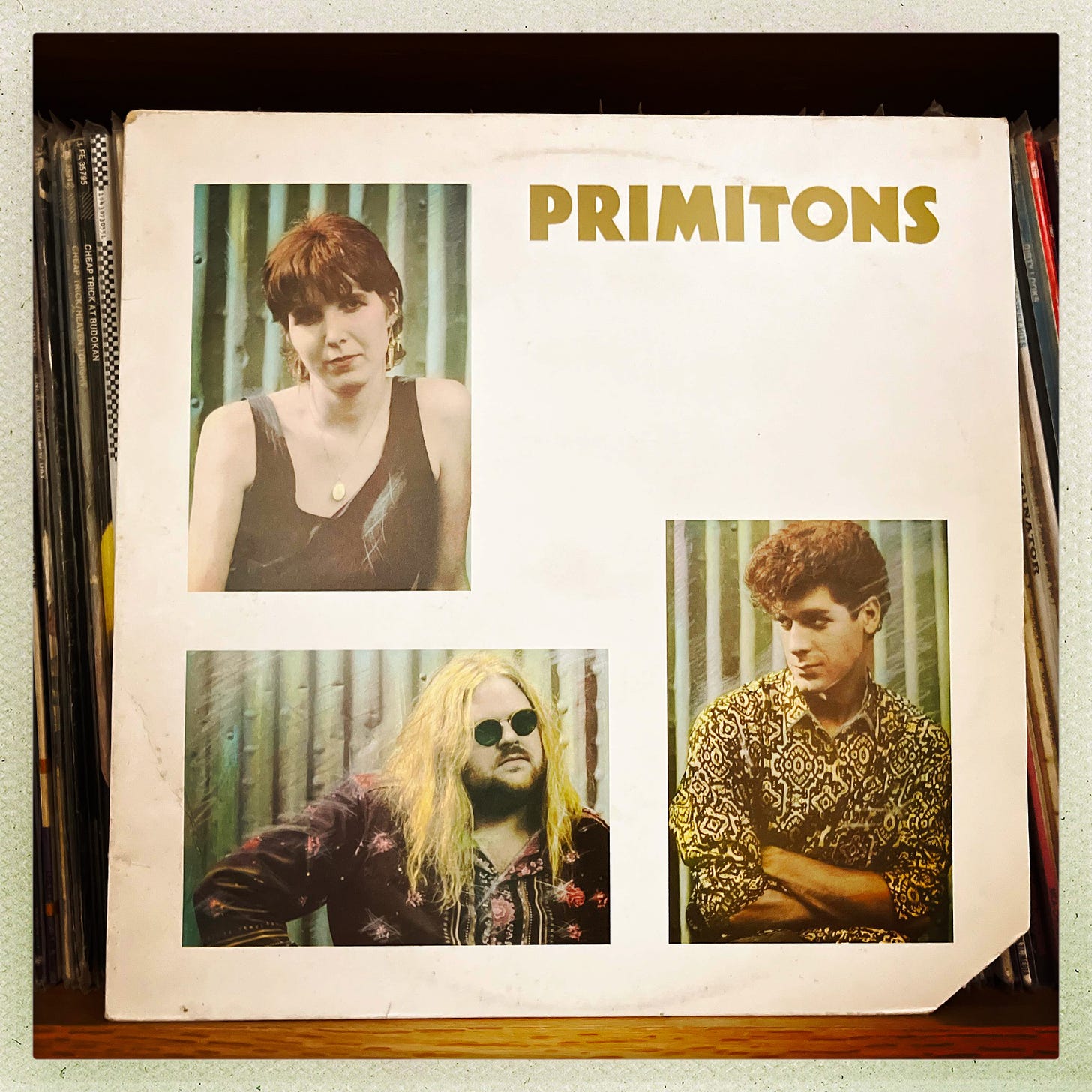

In the mid-1980s I was a DJ at WMUC, the radio station at the University of Maryland where I was an undergraduate student. I had a weekly show (which I’ve written a bit about here) and a regular highlight was poring through the new releases that would arrive, vouchsafed by a kind of magic: dozens of LPs and 45s stacked haphazardly in a tiny room where DJs were free to preview them. In the fall of 1986 I chanced upon a new three-song 12” EP by a band called Primitons. I knew nothing about them—only later would I discover that I’d missed their debut mini-LP produced by Mitch Easter, whose band Let’s Active I dug, released on Throbbing Lobster, a label that I really dug, and that they hailed from Birmingham, Alabama of all places, and counted a transplanted Swede among their otherwise southern fried members as well as a non-performing lyricist.

In any event, before—well, often during—my radio shows I’d throw onto the turntable anything that looked remotely interesting, and I still remember hearing the opening of “Don’t Go Away” for the first time (the song was band-written with an additional credit to bass player Don Tinsley). A growling riff pushes open a door, a drummer with a snare-and-tom groove follows him inside, and a ringing guitar welcomes them both. (Mots Roden’s playing the guitars, Leif Bondarenko is on drums.) The scene, set in twelve seconds. The mood’s anxious, as if someone’s impatient to get things started. It’s also danceable as hell, and it rocks. The dissonance between the guitars (one hitching up its pants, ready to cause some trouble, the other sweetly chiming) signals that something’s coming, and it arrives swiftly as a descending dooh-dooh-dooh-dooh vocal line, harmonized with a high drone, that smartens up the players and settles the groove, the three chords shuffling beneath a chaperoning acoustic guitar. I like that the vocals leads with a wordless chant—before Roden can gather his thoughts, he lets the melody do the work. (Stephanie Truelove Wright wrote the lyrics.)

Yet the words that do arrive in the first verse are hard to make out—Roden oddly annunciates Wright’s lyrics, perhaps a consequence of singing in non-native English, and the sentences come across as, and in, a kind of code, a private expression but still deeply personal, the band playing quieter in an attempt to make it out. Stray phrases (did you even notice when, surprised as a child) rise to the surface, but, listening, the impression is of reading a water-stained love letter, much of it illegible but to the writer. Then the chorus arrives, and the title phrase slide in on a shaft of light. Answered by backing vocals, Roden tags a light-hearted hey-hey to his aching appeal, not wanting to look too needy or desperate. But he’s already written the song, or it’s written him. In the second verse, Roden clears his throat and lands a killer line—

Like an ancient highway with the memories of a sign

Upon and to the sky, seek and you shall find

—that focusses things. The path I need is this way, only the exit sign is gone. A hell of an image desire and loss, the preoccupations of most great pop songs. Does Roden bury himself further by singing “On the way” as the second chorus? (He even gives himself an extra, hopeful bar.) On some days he sounds roundly confident, on others delusional.

So many epiphanies arrive in a song’s bridge, where a key or a chord change mimics the singer’s slight turn away from what they’d just been singing about, toward the song’s real subject. In “Don’t Go Away”’s bridge, we’re in a philosophical realm:

If this world is turning, then I’m turning with it, too

It won’t stop whichever way I choose

Everyone plays the game, he sings next, win or lose, this song’s version of the head-clearing moment when a songwriter realizes that they’re not writing and singing only about themselves, but about all of us. In a great surprise, a guitar solo from Roden erupts and claws at the fabric of the song, a beautiful few bars of aggression and distortion that, in this context, feel as if they’ve been imported from an unruly garage band down the street, until you realize that Roden’s been energized by the relief the clarity of that bridge has brought him. The world won’t stop and I’m along for the ride, so let it rip. Fuck it. I’m gonna channel Ron Asheton.

Roden retreats back into mumblesinging in the next verse, to my ears anyway, and at the time I not only forgave him for it, I extolled him. This was the era when Michael Stipe’s vocals were nothing more than another musical instrument, his infamously undecipherable lyrics part of his band’s great mystery and appeal. And none of it really mattered anyway given “Don’t Go Away”’s bright, ecstatic chorus—which poignantly rides out the song entwined with the words to the bridge—so plaintive, clear, and quietly desperate that it sheds light into the shadowy, unknown corners of the song. A sonic translator, of sorts.

I’m sometimes wary of listening to music that had a tremendous impact on me in my early twenties; time has a way of recasting a favorite song as a harmless background character in a sitcom set in whatever decade you turned twenty or twenty-one. A few years ago, I pulled out a cherished album by the Windbreakers, guarding against disappointment as I dropped the needle. (I was pleasantly surprised.) The commercial titan pop producer Max Martin has remarked that “A great pop song should be felt when you hear it.” Sure enough, yet the body changes over time. When I listen to “Don’t Go Away,” I find I’m not tethered to that particular spot to where Hornby figured his favorite song would forever take him—I marveled at “Don’t Go Away” the afternoon I spun it on my radio show nearly forty years ago, and I marveled this morning, too, listening to it for the hundredth time. The blend and balance of melody, hooks, playing, and eternal lyrics have kept the song aloft, above the circumstances of its being felt, then written, then played, and then recorded—all specific moments in place and time—as it drifts into its future.