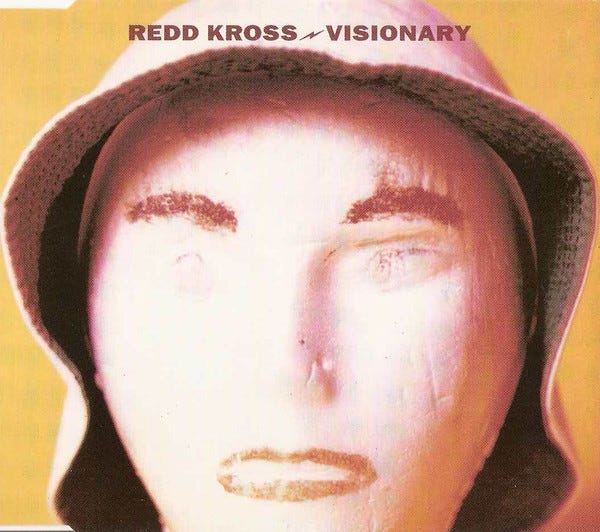

A song can be so rousing that it works in any context: a massive arena, a low-ceilinged dive bar, a basement, a bedroom. Plugged in and unplugged. Redd Kross’ “Visionary,” from the band’s fourth album Phaseshifter, released in 1993, is just such a tune.

Written by band founders and brothers Jeff and Steven McDonald, “Visionary” opens with its chorus, as if it won’t wait any longer than it has to to make its demands. Really, it opens with a monstrous riff from guitarists (Jeff) McDonald and Edward Kurdziel—muscled by (Steven) McDonald on bass, Brian Reitzell on drums, and Gere Fennelly on keys—a clawing, gasping climb up the mountain to some guru. Upon arrival, in thin air, the song catches its breath before making its claims. No, really: the song begins with a snippet of mutterings from the band members; it sound like they’re saying and then shouting back and forth to each other the words “one” and “two” like a studio in-joke, a goof on the studio vérité of “Taxman.” Yet once you’ve heard the song and listen again, that babbling begins to sound like feverish, apostolic chanting. Fuck irony, I need saving.

The McDonald brothers sandwich the first verse between two takes on the chorus, the first of which raises the stakes within moments by addressing a startled, now complicit listener: “I’m looking for a visionary, someone just exactly like you.” The second chorus complicates things a bit:

I’m looking for a visionary

Because I guess I want somebody

We all need somebody

Looking for a visionary

And that savior is you

I love the way the melody descends slightly in the first two lines and than firmly grounds itself with Reitzell’s demanding four-four, the doubt turned to clarity. The qualifying vulnerability in “Because I guess I want somebody” and the desperation in “We all need somebody” either threaten the singer’s resolve or lay bare his bracing honesty, or both—your call. Either way it’s clearly a human singing.

I think what we can all agree on is the ferocious punch of the band’s playing, musicians fully committed to translating the singer’s needs. Phaseshifter came out in an era of great rock and roll songs that sounded great really loud—think Nirvana’s “Stay Away,” Mudhoney’s “Touch Me I’m Sick,” Hole’s “Violet,” the Fluid’s “Black Glove” and their righteous stomp through the Troggs’ “Our Love Will Still Be There,” and the rest—and “Visionary” benefits from really cranking it. Some fans down the years have decried the album’s of-the-era production, in particular the deck work of engineer John Angello. One wag online described the album’s sound as “grungerama.” Here’s Robert Ham a few years back in Pitchfork:

Although Phaseshifter was produced by the band…the thick, brawny sound of the record owes everything to John Agnello, who recorded and mixed the sessions. Perhaps an attempt to apply some hard-rock spunk to their power pop, in the vein of Andy Wallace’s work on Nevermind, the unfortunate results turn hip-swingers like “Jimmy’s Fantasy” and “Visionary” into headbangers and almost entirely bury Fennelly’s contributions.

I agree that Fennelly’s playing is sadly muted in the final mix, but I can’t agree with Ham’s dismissal of “Visionary” as merely a headbanger, reducing a fervent plea to something far less complex and stupider-sounding. A “hip-swinger”? The action’s in the heart and head, as well.

The chorus is so good, so electrifying and moving that it threatens to out-glare much of the rest of the lyrics. Would you want to be labeled a “savior”? I’ve never found the McDonald siblings commenting directly anywhere, but I wonder if the song’s in part about Kurt Cobain, who’d be dead within six months of the song’s release. Cobain certainly bristled under the “savior” “spokesman” tag that was foisted upon him, the requisite, unwanted contradictions, pressures, and ironies difficult for him to bear let alone make sense of. “You killed the superstars, the superstars of punk.” “You fed the demons inside.” “Strung out on lies, strung out on junk.” The lyrics can support that reading if I want them to, though I’m not sure I need them to.

Instead, I like the generalizing quality in the following verse—

Is it nice to be the one with the eyes

And lead us all astray

Always proud keep our knees to the ground

I’ll be your whore, I’ll give you more

where the one who the singer is admiring could be anyone, really, a popular figure, a girlfriend, a boyfriend, a mentor, any stranger rendered divine by drugs or exhaustion or the lighting in a bar. Anyone with a vision so clear and persuasive as to drop their followers to their knees, whoring themselves for more. Of course there’s danger in those lyrics, room for deep disappointments and reckoning. Yet the need to stray from the norm, to follow a leader, is so strong—it’s voiced in the frantic, Ace Frehley-esque guitar solo—that it’s finally unquenchable. At least for these four minutes.

If Pete Townshend isn’t damn jealous of “Visionary,” he should be.

On far too many dark days to count, I fear that I might expect too much from rock and roll, that I’ll read too much into a song because of my own needs. Perhaps “Visionary” is working on a sardonic or a sarcastic level that I’m missing for my own earnestness. Maybe McDonald’s singing with a half-grin and an eye-roll that I can’t see, sending up the song’s urges. (Or perhaps the song’s more menacing than beseeching?) I know Redd Kross well, know and love their pop culture indulgences and day-glo sensibility; when I caught them at The Metro in Chicago four years ago the mood was fun and goofy, leavened with a seriousness that the band didn’t take all that seriously. Yet beneath the best songs was an urgent current—the McDonald brothers know deeply how lives can be shaped by a summer of Top 40 music. And all I know is what “Visionary”’s sublime, euphoric chorus, and those loud guitars, tell me. It can’t be a joke.

About three quarters of the way through, the band breaks down and a guitarist strums, alone, for a few bars. Your ears are still ringing. It feels as if the song’s demo has been punched in. It makes you wonder what a stripped-down “Visionary” might sound like.

On September 16, 1993, in the midst of a two-week U.K. tour, Redd Kross traveled from England to Hilversum, Netherlands to tape a show at NOB Studios for 2 Meter Sessie, a radio and television program. (They were back in England the next night to play a gig in Stevenage.) Phaseshifter would drop in three weeks. Nobody had heard “Visionary” yet.

“I’d say it’s harder to play with an acoustic guitar strapped over your shoulder for a few hundred people than it is to play in front of thousands with an entire bombastic band behind you.” That’s Cheap Trick’s Robin Zander, who it’s safe to assume the McDonald brothers hold in high esteem. McDonald and (presumably) Kurdziel surely felt the intimacies in NOB Studios as they fingered the fret boards of their guitars in preparation for playing an acoustic version of “Visionary.” (Also taped that day was “Lady in the Front Row” from Phaseshifter, the non-album “Switchblade Sister,” “I Don’t Know How to Be Your Friend” from 1990’s Third Eye, and a cover of Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers’ “That Summer Feeling.”) How would the song work—would it work—as an acoustic number?

The opening riff, played here by a single guitarist, certainly suggests something vastly different than what the full band’s roar portended. Now we’re alone—that is, alone with the singer—but where? His bedroom, his car, somewhere-the-morning-after is what the mood tells us as he forthrightly lays out the riff. It’s funny how a melody played on a single string of an acoustic can suggest a line of thought; all of the beautiful, melodic noise made by the band, you realize, is the muscle that rouses the distracted singer into action. Here, we’re still in repose.

Turns out that we’re not alone. The harmonies throughout conjure more than a couple of singers—I imagine a line of would-be believers trailing the two—and remind us that this isn’t only one person’s dilemma. Yet McDonald’s singing in the verses is naked, and raw, with a bit of road-burn at the edges, more to evoke his complicated needs. Things feels real personal in the verses—McDonald can’t hide behind an ironic sneer in “You killed…the superstars of punk” this close-miked. And dig his desperation on the line “The abyss is all it is” in the bridge. Turns out that that might be what the song’s all about.

I wrote recently about the appeal and limits of demo recordings. The vibe’s similar here in this Netherlands studio, but since the song’s already been finished—performed, recorded, and mixed—the energy’s easy to recapture, everything still humming for the players even as they’re figuratively unplugged. The solo naturally lacks the firepower of the band version, and the chorus misses Reitzell’s emphatic, almost angry fills and the magic touch of the reverb on “I” and “we,” sending those words thrillingly aloft above communal, arena-sized desires.

Yet as a kind of late 20th century quasi-folk song, this version of “Visionary” works, reminding us that all great art begins in the dark inside of the artist. The acoustic version is a little bit closer to its origins.

Such a great song, from what is some days my favorite Redd Kross album. That the Pitchfork writer (or anyone) would use the phrase "unfortunate results" in connection with Phaseshifter is absolutely mind-boggling to me.